Is DuckLake a Step Backward?

Examining the new open table format’s return to relational metadata management

When I first read Kafka creator Jay Kreps’ article about logs (and his subsequent book, I ♥ Logs), I was fascinated by the elegance of immutable, append-only sequences of records.

Logs represent one of the simplest yet most powerful abstractions for managing data on physical storage. Since the invention of Apache Kafka and similar log-structured systems, the big data community has embraced the simplicity and scalability of log-oriented semantics.

This paradigm shift manifested most notably in modern data lakehouse table formats like Apache Iceberg, Apache Hudi and Delta Lake where—unlike traditional database implementations—all metadata operations are captured in immutable logs stored alongside data files on cloud storage such as S3.

But then comes DuckLake, a new open table format introduced by the DuckDB creators who have boldly rejected the log-oriented metadata philosophy.

These contrarians seem determined to challenge big data and distributed systems conventions built over the last decade. First, they built DuckDB to argue you don’t need distributed systems like Spark for majority of workloads. Now they’ve built DuckLake to claim you don’t need distributed metadata logs and Iceberg!

This article is going to examine DuckLake’s metadata design in comparison to current and previous generation table formats.

To do an architectural comparison, first let’s look at the primary design goals of modern log-oriented table formats.

Log-Oriented Open Table Format Design

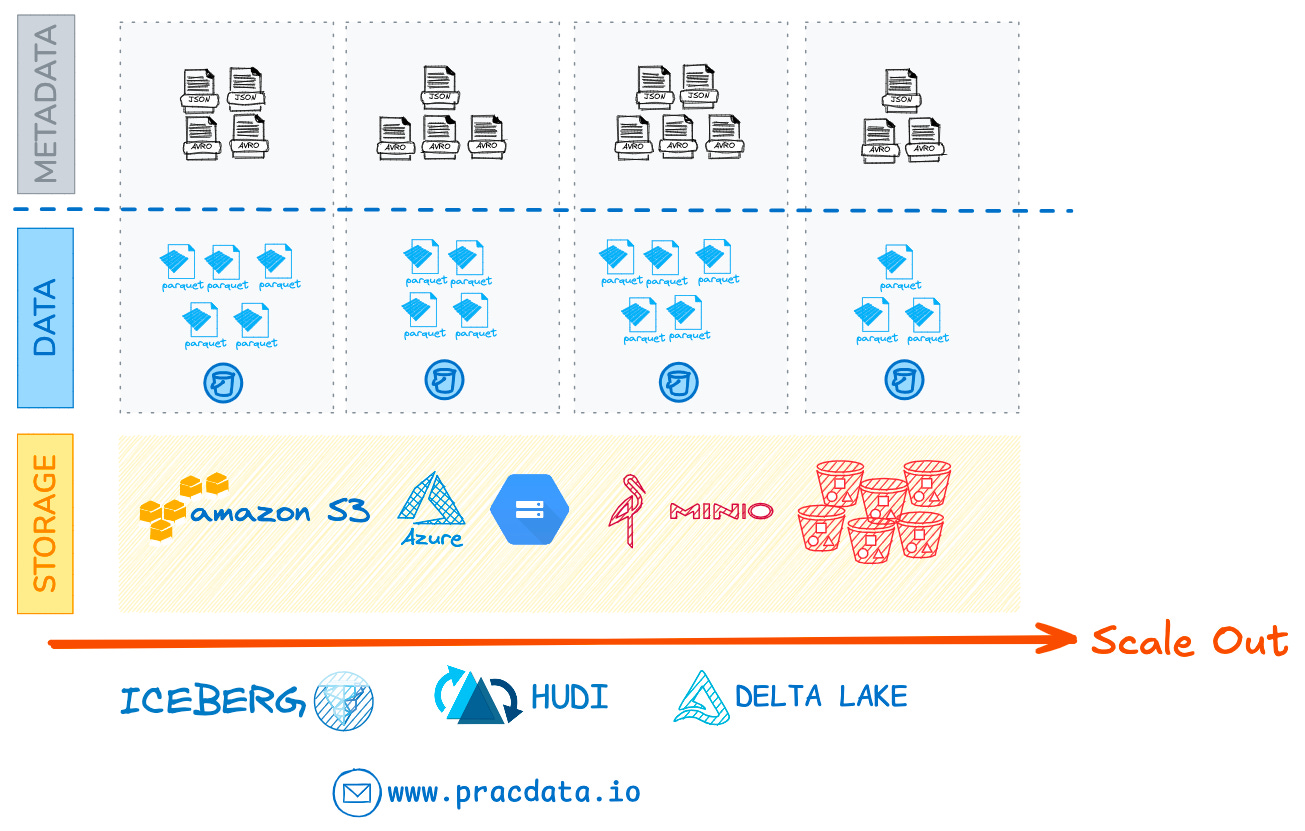

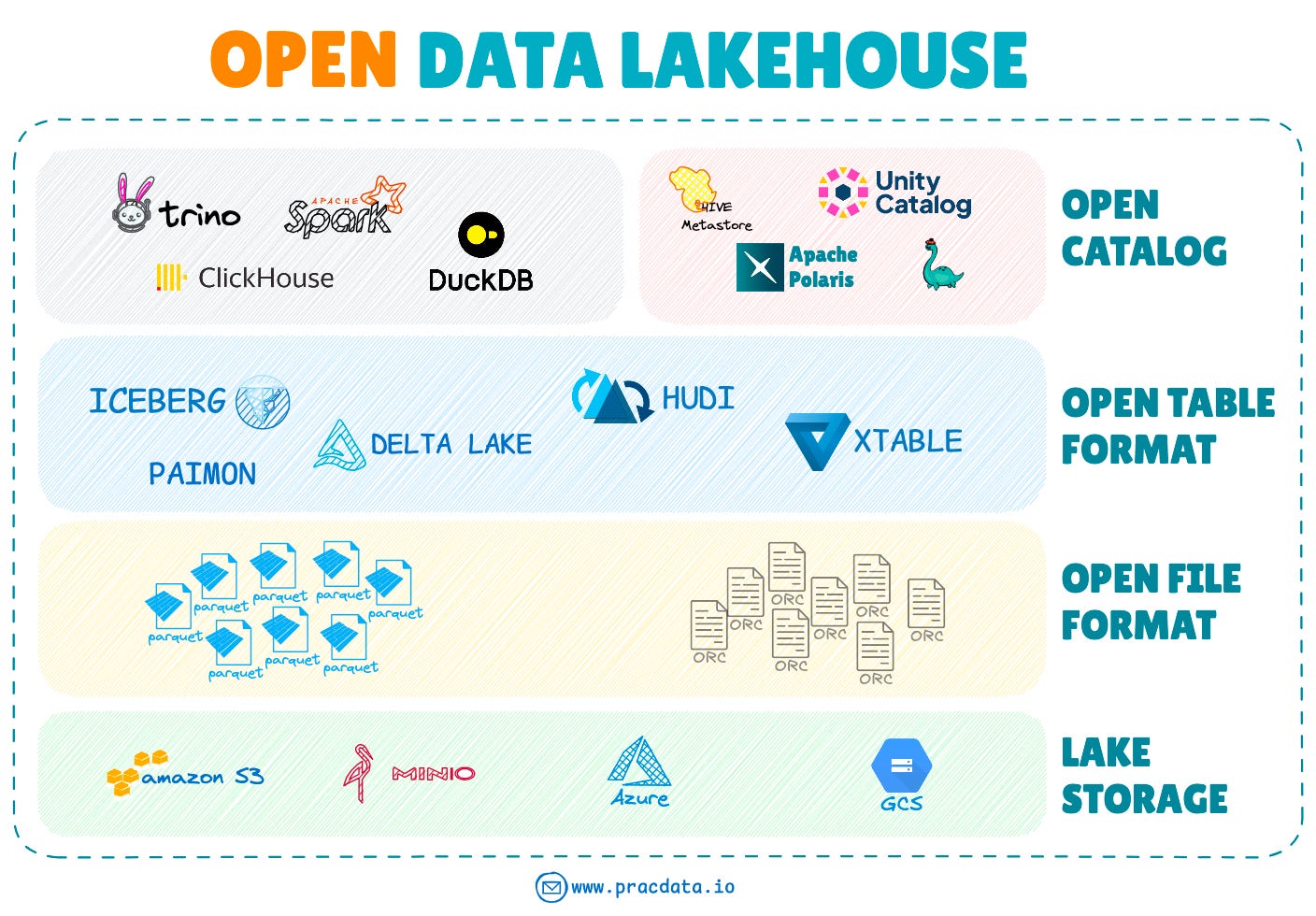

Modern open table formats store metadata in immutable files right alongside the data for each dataset in object storage. Why is that advantageous?

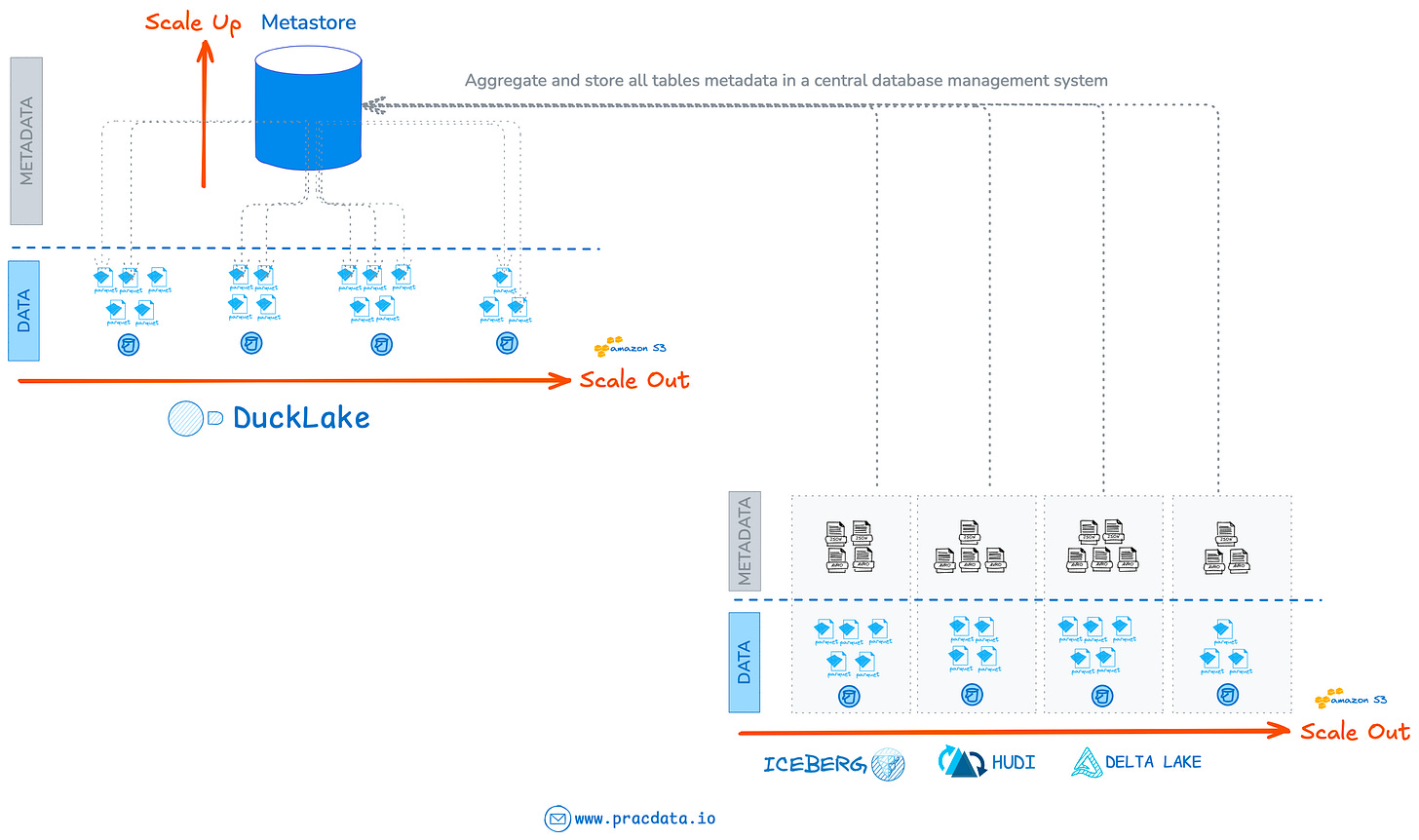

This enables independent, horizontal scaling of both data and metadata. There’s no need to manage external metadata servers, no backend Metastore to become a choke point, and a single protocol (storage REST API) to handle everything, both data and metadata.

With this scalable architectural foundation, open table formats such as Apache Iceberg, Apache Hudi, and Delta Lake have emerged as the dominant approach for managing data on cloud object stores.

Now, with DuckLake entering the scene, an obvious question arises: why build yet another lakehouse table format when the market already seems saturated? What gap could DuckLake possibly fill, and what makes it different from existing table format architectures?

To answer that, let’s first briefly recap how we got here and why major open table formats adopted their current log-oriented metadata architecture.

Understanding this history is essential because DuckLake’s design bears similarities to the previous generation Apache Hive system.

The Hadoop & Apache Hive Era

In the Hadoop era, Apache Hive (+ Hive Metastore) served as the dominant table format on data lakes.

However, Hive suffered from two critical bottlenecks that motivated top tech companies like Uber and Netflix to develop new table formats for managing petabyte-scale data lake platforms:

1. Slow Metadata Operations During Query Planning

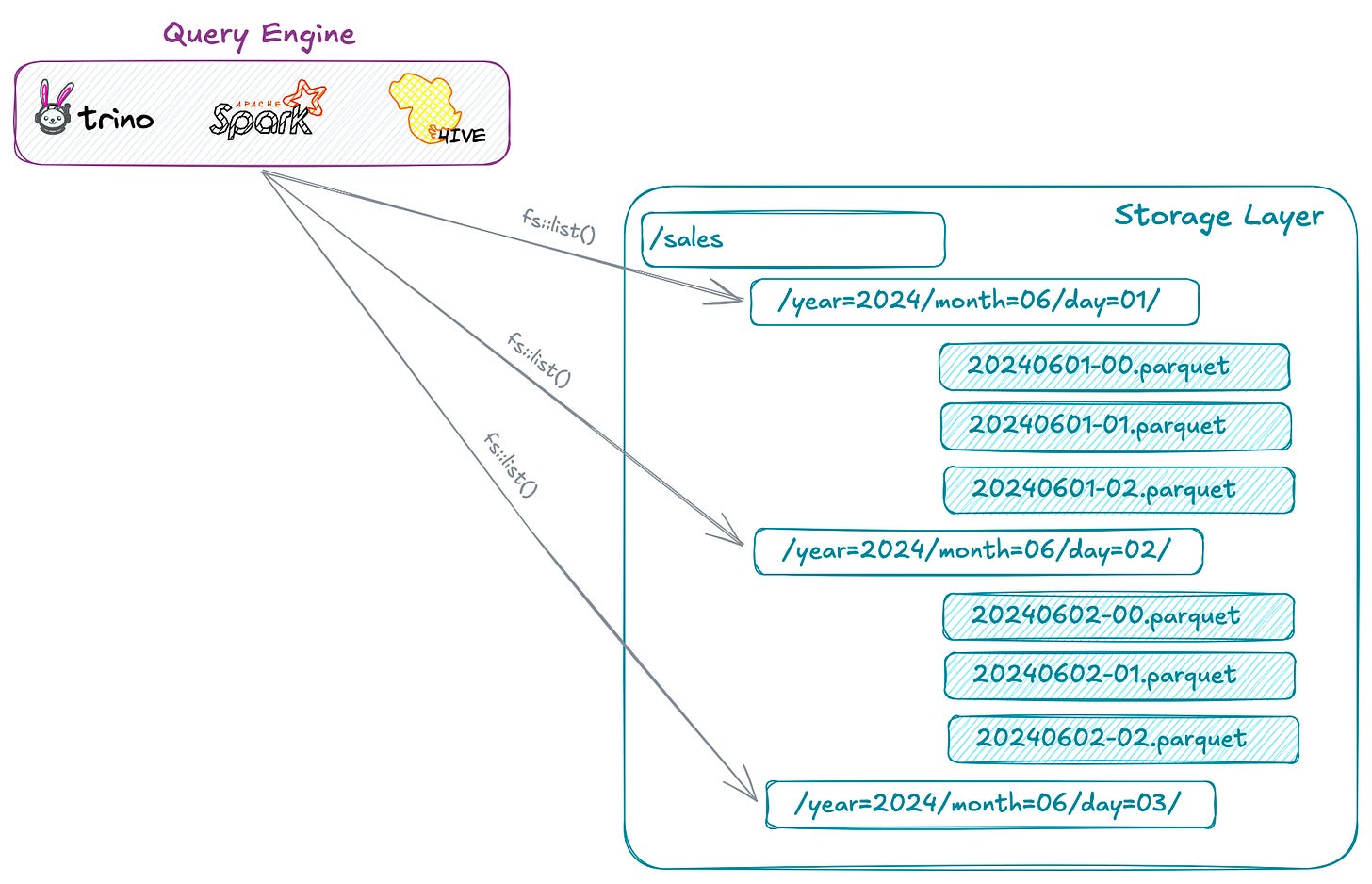

Hive table format was a directory-oriented format that relied heavily on directory and file listing operations during the query planning phase.

The critical problem for Netflix and similar companies managing their big data platforms on cloud, was that Hive table format was architected for Hadoop HDFS, not cloud object storage like S3.

When migrating from Hadoop HDFS storage to cloud object storage like S3, the I/O patterns change dramatically: fast local RPC calls are replaced with slower REST API calls. Additionally, cloud storage introduces new constraints such as Per-API-call charges, API limits (e.g., 1,000 objects per list operation) and rate limits that didn’t exist in Hadoop/HDFS environments.

For tables with millions of data files across many partitions, query planning becomes both painfully slow and expensive.

Listing all files, issuing HEAD requests, and reading metadata sections from millions of Parquet files—each with network round-trip latencies up to 100ms—creates a significant performance bottleneck.

2. Inefficient Transaction and Mutable Data Management

Beyond performance issues, Hive lacked efficient transaction and concurrency management, and relied on pessimistic locking mechanisms often resulting in long lock contentions.

To make matters worse, other engines like Trino didn’t respect Hive’s locking mechanisms and bypassed them entirely, creating data consistency risks.

For a deeper dive into this history, I’ve previously written a comprehensive two-part series on the evolution of open table formats:

Emergence of New Open Table Formats

Facing these limitations, tech giants like Netflix and Uber recognised the need for a fundamentally different architecture. A new table format that can handle massive workloads far more efficiently.

Two key design requirements emerged to improve query planning performance:

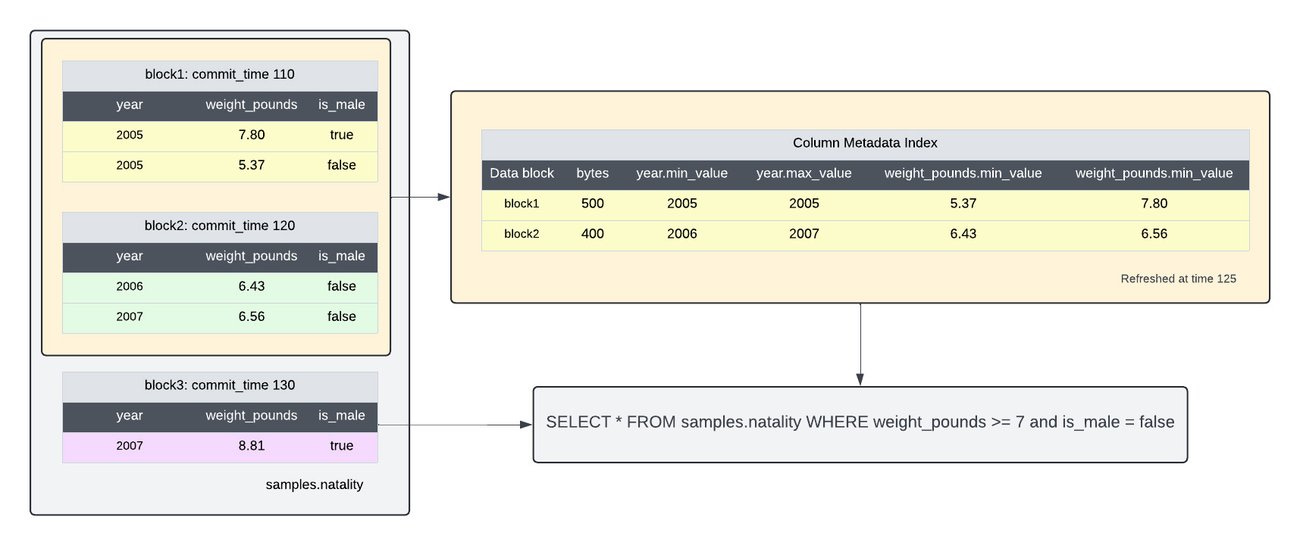

1. Store the list of all data files in the metadata layer to avoid excessive and slow object listing calls to storage APIs during query planning.

2. Store data file column statistics (such as min/max values) in the metadata layer to eliminate the need to read and parse built-in column stats from each Parquet or ORC data file at query execution time, enabling efficient file-level data file pruning (often referred to as predicate pushdown) right at the query planning time.

But this raised a critical question: where should these massive amounts of file and column statistics be stored?

For a typical petabyte-scale data lake with hundreds of millions of data files—and tables averaging around 10 columns—you’re looking at billions of metadata records for column statistics alone.

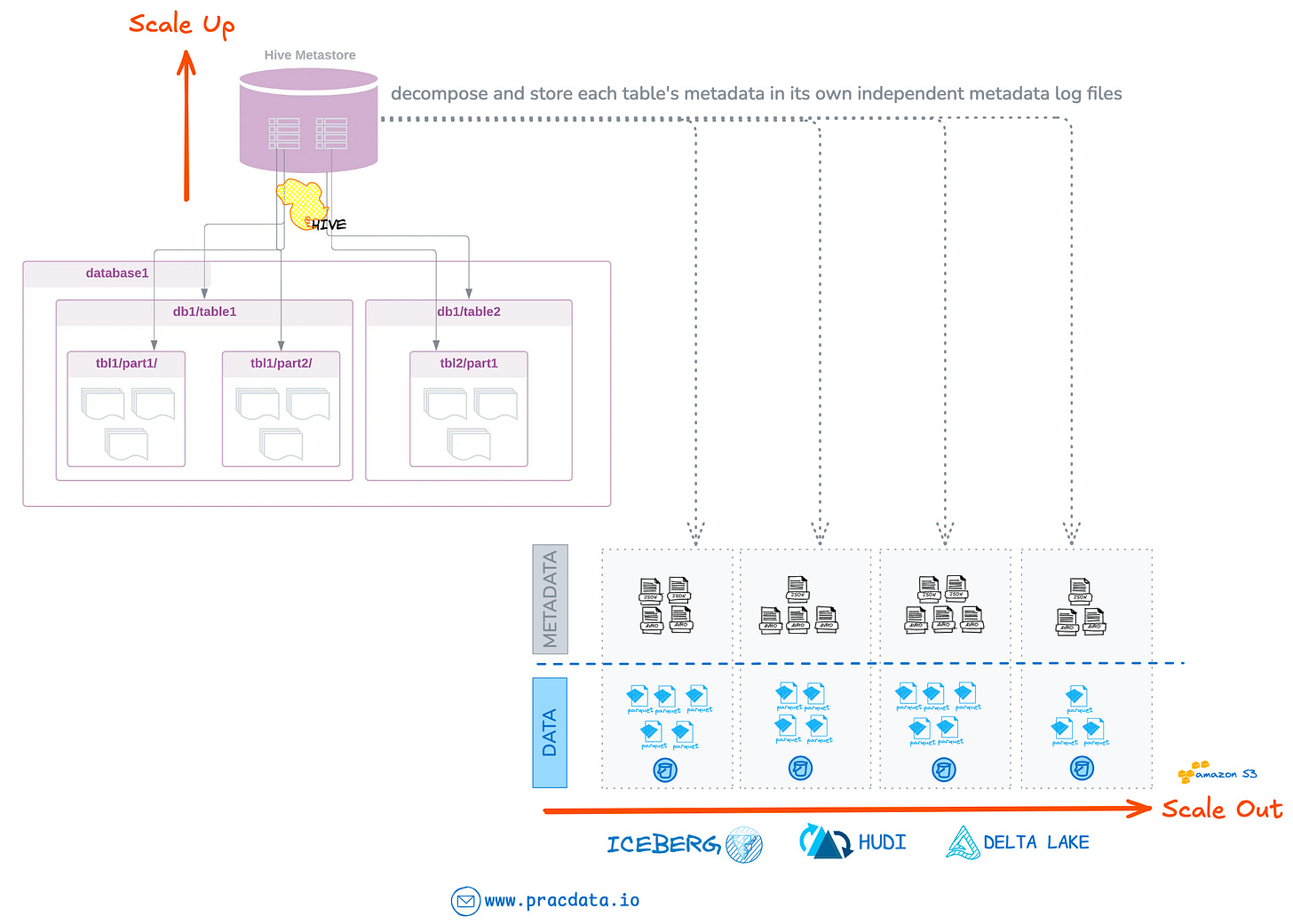

I imagine the engineers designing these table formats took a hard look at Hive Metastore’s architecture and quickly rejected the idea of storing such massive metadata volumes in a centralised database system. Even with continuous scale-up efforts, Hive Metastore was already becoming a bottleneck—adding billions of metadata records would only make matters worse.

Combine this realisation with the proven scalability of distributed logs, and storing all metadata on object storage became the obvious choice. This approach delivers a shared-nothing metadata architecture with theoretically infinite scalability.

Similar to how data files are distributed, metadata is partitioned per dataset, allowing each table to manage its own metadata independently.

With this design, a table’s metadata can grow linearly with the data itself without ever becoming a system-level bottleneck.

This design has made many database architects sceptical. After all, HTTP wasn’t designed for the low-latency, high-concurrency demands of database storage—particularly for metadata management, which requires fast reads, writes, and atomic updates.

Despite these scepticism, modern open table formats have gained widespread adoption across the data community.

This widespread adoption of log-oriented formats might seem like vindication of the architecture, but success doesn’t mean perfection. Every design involves compromises.

The Tradeoffs

No design comes without tradeoffs. The pain just shifts from one layer to another, and the distributed log-oriented metadata architecture is no exception.

But what could possibly go wrong? On paper, it all sounds great. In practice, things get complicated.

It turns out metadata has fundamentally different performance and management characteristics than data itself. While large-scale data processing optimises mainly for high throughput, metadata needs to be written, read, updated, deleted and rewritten quickly, reliably, and atomically with low latency.

By design, object stores are not the best match for such workloads.

Challenge #1: Metadata Amplification & Operational Complexity

A major issue with new-generation open table formats is excessive metadata file generation.

Since underlying storage is immutable, each DML operation (insert, update, delete) requires creating a new (or multiple) metadata log file.

In Iceberg, every write generates a new Manifest file, a new Manifest List, and a new JSON Metadata file. On platforms with heavy updates, millions of tiny log files can be generated in a short period of time.

This quickly becomes counterproductive without constant housekeeping to merge and remove obsolete log files. Ironically, the original goal of log-based metadata was to eliminate excessive storage API calls during query planning—but now the problem has simply shifted to a different layer: metadata itself.

How is this handled? Through constant housekeeping operations: expiring older snapshots, background compaction jobs continuously merging small metadata log files into larger ones and dropping obsolete files.

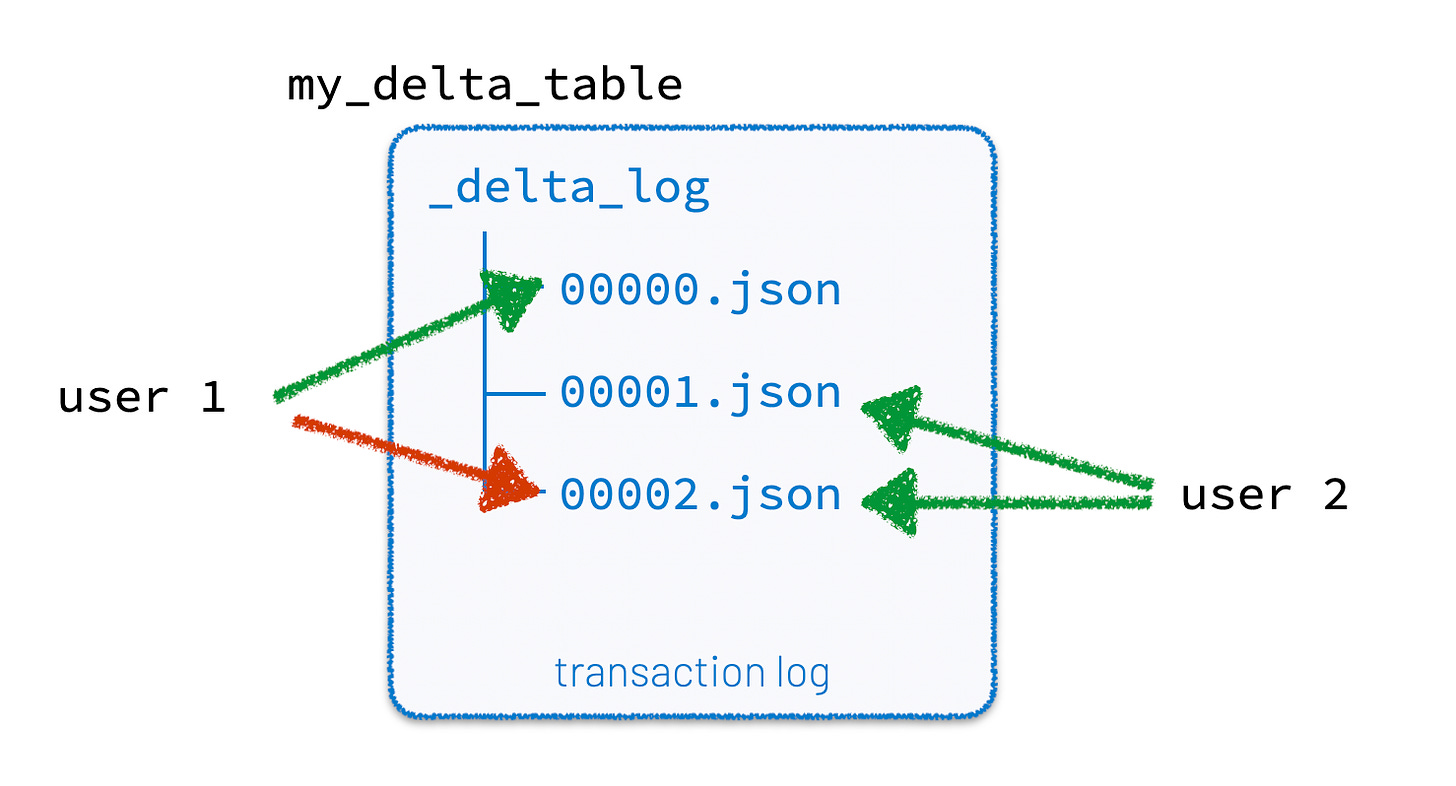

Challenge #2: Atomicity & Concurrency Control

While all new open table formats support read-write isolations through Snapshot Isolation and MVCC, Atomicity on the storage layer and support for multi-write concurrency control (to same object) have been challenging across different storage backends.

Most distributed cloud storage systems lack full ACID compliance and typically provide only eventual consistency guarantees. For instance, AWS S3 doesn’t support atomic file renames. Atomic put-if-absent only became available on AWS recently.

Apache Iceberg relies on an external catalog’s atomic commit (such as a transactional database) for atomically update the pointer to the latest metadata file containing the latest snapshot Id.

To support concurrent writes, Delta often uses a lightweight external lock (commonly DynamoDB-based) to coordinate exclusive access to the log files during commit to deal with race condition of two writes trying to create the same log file (with same version number).

Apache Hudi additionally supports table-level locks through external services such as Zookeeper, Hive Metastore, or DynamoDB to coordinate concurrent writers.

Challenge #3: Dependency on External Catalog Service

The third major challenge is the lack of a native fully-featured catalog. This partially explains the data catalog wars in 2024, when major vendors competed to become the dominant catalog service for data lakehouse platforms.

While schemas are stored and evolved within the metadata layer, allowing direct table interaction without a central catalog, these formats lack the infrastructure for scalable data discovery, governance, and business-level metadata management that users and external query engines require.

The following diagram shows a typical open lakehouse architecture, with an open catalog as a key component of the architecture.

Having outlined these challenges, it’s worth revisiting Hive Metastore to recognise its inherent strengths despite its weaknesses and scalability issues.

First, it was backed by transactional SQL databases such as MySQL and PostgreSQL, which made managing metadata operations in a concurrent, transaction-safe manner straightforward with full CRUD support.

Second, the Metastore served dual roles as both the metadata backend and the catalog for managing schemas. This meant users and all external query engines—Athena, Spark, Trino, Presto—could access and manage schemas directly through Hive Metastore component without requiring any other external catalog service.

These observations set the stage for understanding DuckLake’s philosophy.

Back to DuckLake

Now that we have the required background info let’s go back to DuckLake.

I believe DuckLake aims to achieve the best of both worlds: return to familiar, reliable, update-friendly, and transactionally safe database systems for managing metadata, while incorporating the query performance and table management features pioneered by modern open table formats.

DuckLake is built on a foundational premise:

Relational SQL database systems remain superior for managing metadata, unlike existing open table formats that rely on immutable log-structured metadata stored on object stores.

The DuckLake creators observed the challenges open table formats have faced over the past five years and reached a surprising conclusion: perhaps using a centralised transactional SQL database for metadata management—as Hive did—wasn’t such a flawed approach after all. The key is to preserve what worked while fixing what didn’t.

What exactly is DuckLake’s critique of the log-oriented approach?

Managing table metadata through scattered, immutable log files on object stores creates significant operational complexity.

The challenges include handling excessive numbers of small metadata files, high latency when traversing and scanning metadata logs, and managing the complete lifecycle of table snapshots, version files, data file metadata, partition information, and column statistics.

Therefore, DuckLake proposes moving all scattered metadata structures back to a familiar, reliable centralised SQL database. But wait... haven’t we been here before? Isn’t this a step backward to Apache Hive + Metastore architecture?

Yes, it’s a small step backward—but moving backward isn’t always a bad thing. The key difference between DuckLake and Hive lies in storing complete data file details in the Metastore.

Remember, one of Hive’s major performance bottlenecks was expensive LIST calls to discover all data files for each query plus column stats gathering during query planning phase.

DuckLake eliminates this bottleneck by tracking all data files and storing column-level statistics for each file in the metadata layer, just like modern open table formats. The critical difference is that these details live in relational database tables rather than scattered log files.

Additionally, DuckLake maintains table snapshot information directly in the Metastore, simplifying snapshot history tracking and enabling snapshot isolation through MVCC.

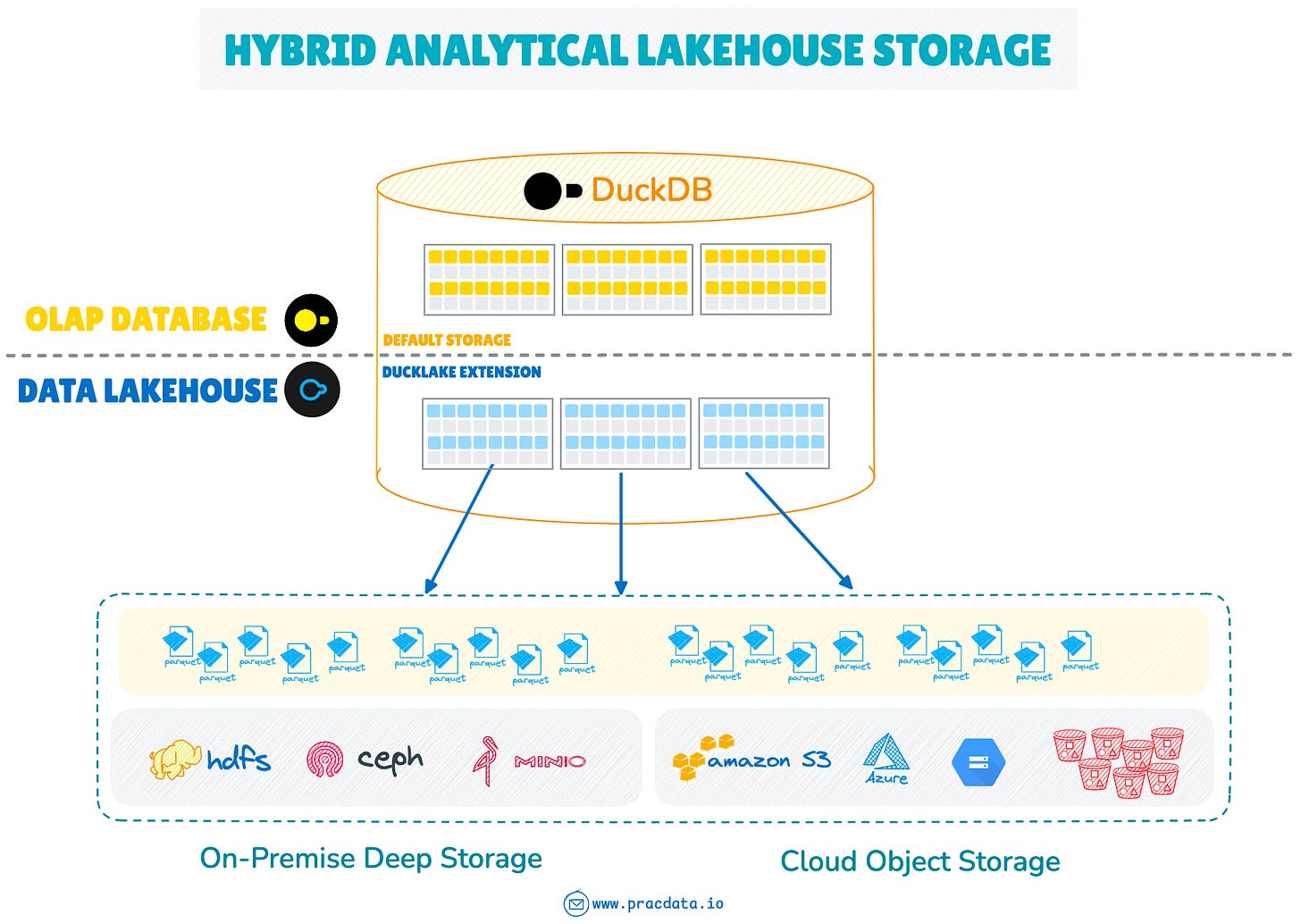

DuckLake follows the proven approach of modern OLAP systems like BigQuery and Snowflake, which successfully manage data on object storage while maintaining all metadata in database systems.

This all sounds compelling—simpler operations, transactional guarantees, familiar SQL interfaces. But there’s an elephant in the room that we must address.

What about Scalability?

Here comes the pivotal question: can DuckLake scale?

After all, scalability challenges were also part of the reason why Iceberg and Hudi were built to replace Hive table format.

A full-featured DuckLake implementation will likely struggle to scale to very large, petabyte-scale platforms, without significant database tuning, vertical scaling and potentially using a distributed SQL database system (ex Neon). However, not everyone operates at that scale—so DuckLake will likely work well without running into metadata bottleneck issues for the majority of workloads.

The Scalability Challenge

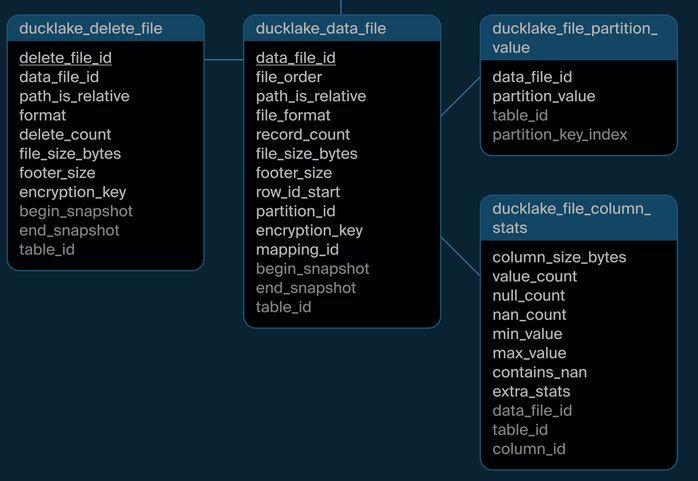

DuckLake stores everything in a centralised managed metadata database. Certain metadata tables will accumulate substantial volume of data:

1. data_file table: Stores the list of Parquet data files for each table

2. delete_file table: Tracks deleted Parquet files for each table

3. file_column_statistics table: Stores column-level statistics (min/max, null count, etc.) for each column in each Parquet file

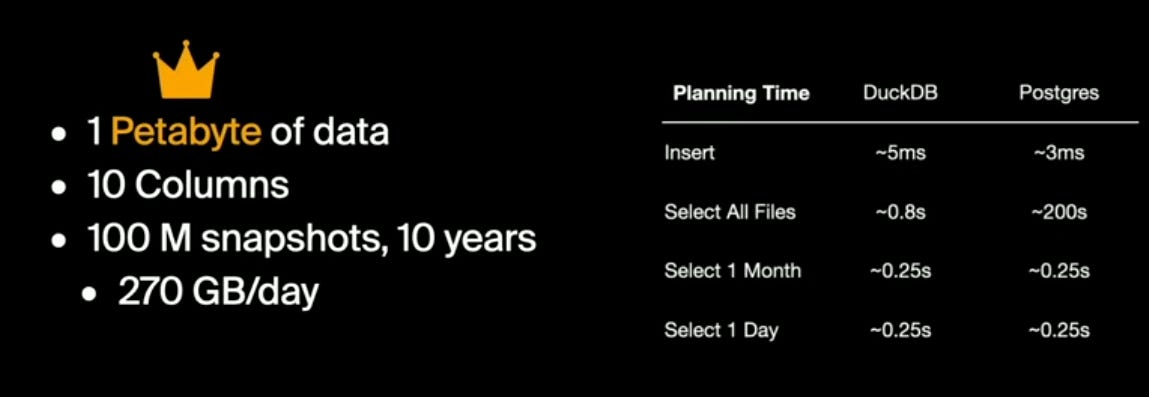

Consider a data lake with one petabyte of data—and we’re not even discussing companies managing tens or hundreds of petabytes. A typical 1 PB data lake contains approximately 50-100 million data files. With optimisation and reasonable file sizes, you might reduce this somewhat, but the order of magnitude remains.

Assuming an average of 10 columns per table, this generates:

100 million records in the

data_filetable1 billion records in the

file_column_statisticstable (100M files × 10 columns)Hundreds of millions of records in the

delete_filetable over time from merge and insert-overwrite workloads

This doesn’t account for historical records from expired snapshots (before expiring snapshots and compaction), which increases volumes further.

Query-Time Implications

Storing and writing to tables with 100s of millions or billions of rows may not present a significant challenge, provided the database server has adequate storage and the tables aren’t heavily indexed in ways that slow down writes.

The real performance challenge lies in querying these tables. Consider querying historical data containing millions of files with many columns. For a typical large query scanning 1 million data files with 20 columns, the metadata stage must:

1. Select 1 million records from the data_file table

2. Join against records from the delete_file table to filter out deleted files

3. Scan 20 million records (20 column stats records per data file) from the file_column_statistics table

However, we don’t need to scan and read all these records. Remember, we’re in the SQL world—we can easily filter metadata and only retrieve the candidate list of data files that must be scanned for matching records.

Here’s a sample query to retrieve the list of data files from a clickstream table where the query filters by event_timestamp column:

SELECT data_file_id

FROM file_column_stats

WHERE

table_id = 'clickstream' AND

column_id = 'event_timestamp' AND

('timestamp-value' >= min_value OR min_value IS NULL) AND

('timestamp-value' <= max_value OR max_value IS NULL);DuckLake Creators’ Perspective

In a recent presentation, Prof. Hannes Mühleisen claims that DuckLake can easily handle petabyte-scale data, citing tests conducted on a table with 100 million snapshots.

Jordan Tigani draws parallels between DuckLake’s column statistics storage and BigQuery’s CMETA metadata table, which serves a similar purpose. However, according to BigQuery’s published research paper on the subject, BigQuery stores column-level statistics separately for each individual table rather than in a single central metadata table.

This means, similar to how existing lakehouse formats manage metadata independently per dataset, there exists a one-to-one mapping between each user table (e.g., sales) and its corresponding column metadata statistics table (e.g., cmeta_sales). This design avoids possible large central metadata tables and enables horizontal scalability.

Similarly, Snowflake stores such metadata on its highly optimised distributed metadata layer, which appears to be built on the FoundationDB distributed key-value store.

As Jordan emphasises, nothing inherently prevents a DuckLake implementation from using a similar scalable and distributed storage engine for the metadata layer.

A vendor with sufficient expertise and resources—such as MotherDuck itself—could reasonably manage such infrastructure, much as Google and Snowflake do. However, for self-hosted deployments, implementing and operating such a system would introduce significant operational complexity and cost.

The Bottom Line

Can the backend metadata server (e.g., PostgreSQL) efficiently manage tables with billions of records and handle many concurrent readers and writers without becoming a performance bottleneck during metadata retrieval and query planning?

This remains to be battle-tested. With a well-tuned database on good-sized hardware and efficiently implemented indexing, clustering or partitioning (or even using distributed database backend) things could work out. But the important thing is to see and weigh out the trade-offs between the two metadata architectural patterns.

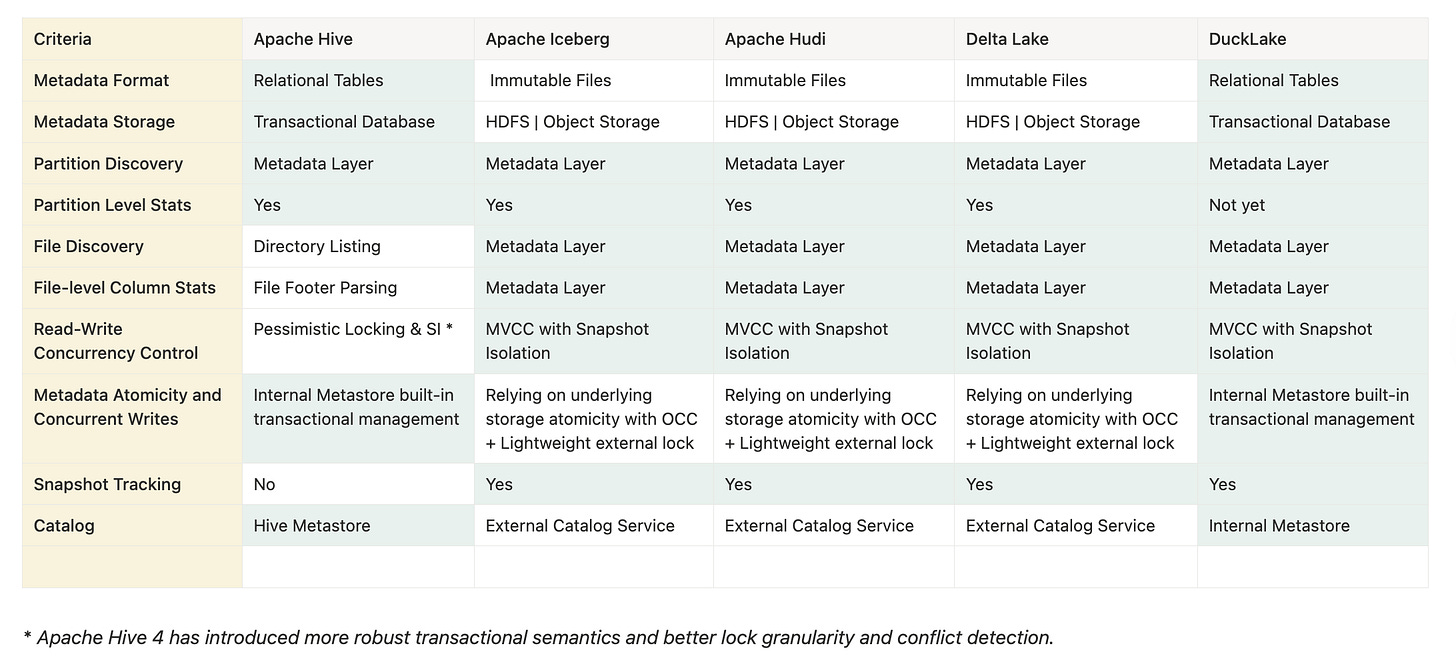

Having explored both architectural approaches in depth, let’s consolidate our understanding with a high-level comparison of key features and design choices.

High-level Feature Comparison

While this blog post is not about feature comparison between different open table formats, here is a high level comparison of some key features and architectural differences between DuckLake and other table formats:

As highlighted in the table above, DuckLake shares significant architectural similarities with Apache Hive while incorporating modern optimisations that address Hive’s shortcomings—specifically data file tracking, column-level statistics, improved concurrency management, and snapshot tracking.

With this technical foundation established, we can now address the central question: what does DuckLake’s future hold?

DuckLake’s Path Forward

It’s still too early to predict DuckLake’s fate. Just months after its launch, it faces fierce competition in a lakehouse market already dominated by established open table formats. The road ahead is challenging if DuckLake hopes to gain meaningful traction.

My personal assessment is that DuckLake has genuine potential, but not necessarily for large tech companies operating at massive scale. And that’s perfectly fine.

While MotherDuck will offer managed DuckLake at cloud scale, the open-source version could find strong adoption among small-to-medium self-hosted data lakes that never approach the metadata bottleneck of billions of records. After all, far more organisations manage small to moderate data volumes (< 100 TB) than operate at extreme scale.

Since DuckDB has already gained significant traction with strong ecosystem integration and support, DuckLake as a DuckDB extension can leverage this momentum.

Together, they could provide a lightweight Hybrid Analytical Lakehouse Storage (HALS) solution.

This represents a simple compelling unified analytics solution for anyone already using DuckDB in production who wants to extend its capabilities to managing data on data lakes.

With the rise of single-node processing paradigm, this solution extends that approach to manage unstructured and semi-structured data processing use cases, where storing data as Parquet files on object storage could deliver cost and performance benefits.

The Ecosystem Challenge

Beyond DuckDB’s territory, DuckLake’s success—particularly as an open-source portable and open table format—hinges entirely on community adoption.

So far in the months since its introduction, no significant contributions have emerged from outside DuckDB-related entities (DuckDB Labs, MotherDuck).

It’s important to note that, like Apache Iceberg, DuckLake is primarily a specification, not an engine. Just as Iceberg has implementations in Spark, Trino, and other engines, DuckLake can be implemented based on its published specification.

To reach its full potential, DuckLake spec requires broad adoption and integration throughout the data ecosystem. This includes support for popular Python data libraries like Polars, DataFusion, and Arrow; connectors for distributed processing engines such as Spark, Trino, and Flink; and data integration services like Fivetran, AWS Glue, dbt, and Airbyte.

Besides tooling, DuckLake requires genuine community interest and incentive to keep pace with the specification’s evolution as it matures over the coming years.

Without this backing, DuckLake risks remaining confined to the DuckDB ecosystem—limited to the DuckDB extension or MotherDuck’s managed cloud platform.

Whether the broader data community sees enough value to invest in DuckLake’s future remains the defining question.

Very well written and thorough article. I like how you walked us through the history of why we are at this inflection point. This always helps ground the reader on the overall purpose of. Thanks, Matt

مثل همیشه ازت یاد گرفتم.

عالی بود